UK armed forces veterans who had ever been convicted of criminal offences, and had served or were serving prison sentences: Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK

Published 10 June 2025

1. Summary

Weighted estimates of veterans convicted of a criminal offence and of veterans who had served prison sentences; unweighted estimates of veterans currently serving prison sentences, by personal and service-related factors, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK

2. Main points

Among veterans who said they had ever served a prison sentence, 44.3% had used support available to veterans in prison (support may not have been available to everyone answering this question) and among veterans currently in prison 62.1% said they had used this support.

Among UK veterans, those aged 30 to 39 years were more likely to have said they were ever convicted of a criminal offence (18.8%) than veterans aged 40 years and over. Males were more likely to have said they were ever convicted than femalesÃ˝(11.4% compared with 2.7%), similar findings were seen among those who were ever convicted and said they had ever served a prison sentence.

Among UK veterans, those who were disabled under the Equality Act 2010 were more likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence than those who were not disabled (12.4% compared with 8.3%), but there was no evidence of difference in the proportion of veterans with a conviction who had ever served a prison sentence by disability.

Whether a veteran had ever been convicted of a criminal offence was associated with financial factors, veterans whose income was £20,799 a year or less were more likely to have been convicted (15.6%) than those whose income was £51,950 a year or more (7.2%) and we see similar patterns among veterans who had ever been convicted and had ever served a prison sentence.

Veterans who served at Officer rank were less likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence (2.9%) or to have been convicted and have ever served a prison sentence (4.9%), than those who served below Officer rank (11.6% and 16.4%, respectively).

The overall percentages reported of veterans who had ever been convicted of a criminal offence, ever served a prison sentence or were currently in prison, should be used to understand coverage only and are not intended to act as an estimate of the real proportions with these experiences within the veteran population. We proactively sent paper questionnaires into prisons across the UK to ensure this group of veterans were captured and there is no way to understand how representative these data are of the actual veteran population.

Qualitative responses from veterans who were currently in prison in this article give more depth and context to how veterans felt they could be better supported.

3. About the Veterans’ Survey 2022

These statistics are official statistics in development. They are published as research and are not official statistics.Ã˝

The following data should not be used to estimate the proportion of veterans who had ever been convicted or who had ever been convicted and had also ever served a prison sentence. The same applies to the unweighted data supplied relating to veterans who were currently in prison. These univariate estimates help to explain who answered the veterans survey which aimed to specifically capture information from veterans with these life experiences. A paper copy of the survey was specifically sent into prisons across the UK to ensure this group was captured. More information about how the survey was run can be found in Office for National Statistics’ (ONS’s) .

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) published initial research on the Veterans‚Äô Survey 2022 in itsÃ˝.Ã˝The survey was partially weighted by age to address undercoverage of older veterans. However, after weighting some biases remained and we know disabled veterans were over-represented in the survey and veterans who had only ever served in the reserve forces were under-represented.

Multivariate analysis is provided in this article and in our , which can be used to understand more about those who were ever convicted of a criminal offence or those who were ever convicted and who also said they had ever served a prison sentence by their personal views, attributes, demographics and service-related factors. We also provide some qualitative analysis of responses from veterans who responded from prisons in relation to support they felt was lacking.

Caution should be taken in comparing proportions of veterans who have served a prison sentence or been convicted of a criminal offence to those of the general population. The veteran population is older and more male than the general population and, as outlined in the Age and sex section of this article and in Statistics on Women and the Criminal Justice System 2023, males were more likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence.

A veteran may have a military conviction if they were found guilty of a crime while they served in the UK armed forces, a conviction might be a dismissal, a service detention, an overseas community order or a service community order. Individuals may have responded to the criminal convictions question based on whether they have a military conviction.

Statistics presented by other sources in relation to convictions may be annual snapshots or present the rate of convictions against prosecutions for a given demographic rather than whether an individual has ever been convicted of a criminal offence.

Estimates for veterans who were currently in prison remained unweighted in this analysis.

We only refer to a difference throughout this article where we are confident this difference is a statistically significant difference. This is based on the associated 95% confidence intervals found in ourÃ˝accompanying datasets. This article focuses on UK-level data only. Additional UK-level data are found in our .

Country-level data is not available for those who ever served a prison sentence or were currently in prison due to small numbers. Findings by country for whether a veteran was ever convicted of a criminal offence are described in the accompanying .

4. Coverage: Veterans who had ever been convicted of a criminal offence and that had ever served a prison sentenceÃ˝

Only veterans who answered the survey without assistance were eligible to be routed to questions about whether they had committed a criminal offence or had ever served a prison sentence. Throughout this article the base used is therefore veterans that answered the survey without assistance rather than all veterans. More information about help veterans could receive completing the survey can be found in ONS’ . Approximately 2.2% of veterans were not asked the question about criminal offences as they had assistance answering the survey.

Among eligible UK veterans, 10.4% said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence that was not a speeding offence. Spent and unspent convictions and convictions before, during or after service should have been included.

A small proportion of veterans had ever served a prison sentence, 2.6%. Only veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence were asked if they had ever served a prison sentence, therefore from this point, throughout this article the percentage of those who ever served a prison sentence are based on those who said they were ever convicted.

Among UK veterans who said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence, 24.8% said they had ever served a prison sentence, with 0.4% preferring not to say. This proportion includes veterans who were currently serving a prison sentence and more information about this group can be found in the Coverage: Veterans who were currently serving a prison sentence section. Data for those who had served a prison sentence but were not currently in prison was not feasible as numbers were small.

5. Findings: When a veteran was convicted of a criminal offence and use of support available to veterans

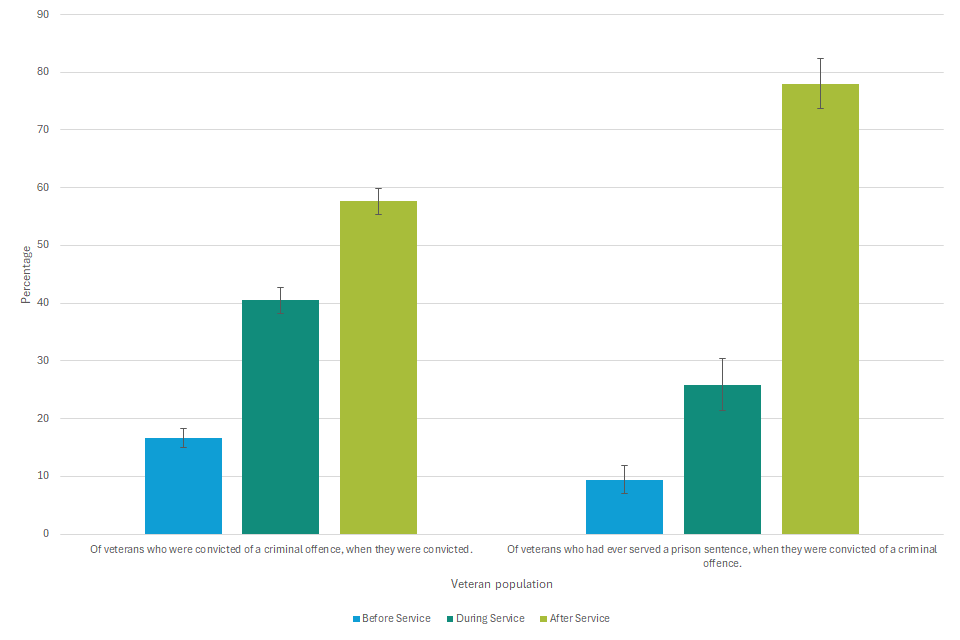

Of those who had ever been convicted of a criminal offence, 16.6% said they were convicted before service, 40.5% said they were convicted during service and 57.7% said they were convicted after service (veterans could have been convicted on more than one occasion and were able to select as many options as applied). Though restrictions on recruitment have changed over-time, spent convictions and less serious unspent convictions do not necessarily prevent an individual from joining the UK armed forces, more information about the requirements to join the UK armed forces can be found on the , , and websites.

Figure 1: Veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence and veterans who had ever served a prison sentence were most likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence after service

Weighted percentages of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence and of veterans who had ever served a prisons sentence by when they were convicted of a criminal offence. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Only veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence were asked when they were convicted.

Respondents could have selected as many options as applicable.

We do not know if when a veteran was convicted related to their prison sentence they served.

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Among those who said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence and said they had used specialist support available to veterans on probation, released on license or serving a community sentence, references to using Soldiers‚Äô and Sailors‚Äô Families Association (SSAFA), Royal British Legion (RBL) and Project Nova were most common.Ã˝

Of veterans who had ever served a prison sentence, 44.3% said they had used the support available to veterans in prison. However, we do not know during what years a veteran was in prison and if support would have been available to all veterans whoÃ˝were asked the question. Veterans who had used the support available to veterans in prison most commonly referenced SSAFA, Care after Combat, Veterans in Custody Support Scheme (VICS)Ã˝and RBL. Support for veterans in the justice system can be found at: Getting help with criminal justice issues as a veteran.

Even though charities like SSAFA and RBL have been around for a long time (founded in 1885 and 1921 respectively), help specifically for veterans in the criminal justice system like Care after Combat and Project Nova have only been available more recently, both were founded in 2014.Ã˝

6. Findings: Criminal convictionsÃ˝and prison sentences by personal demographics

6.1 Age and sex

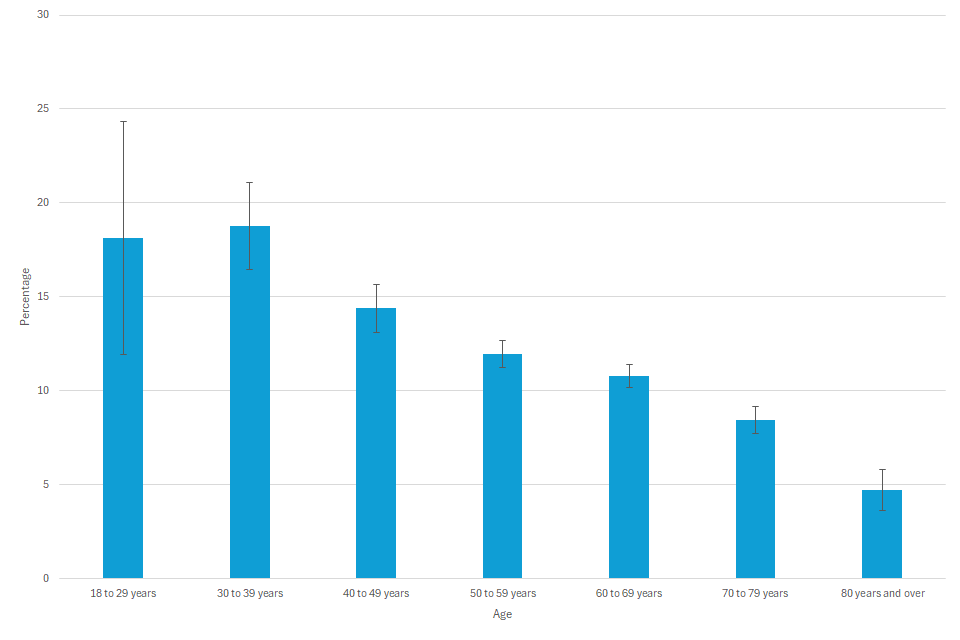

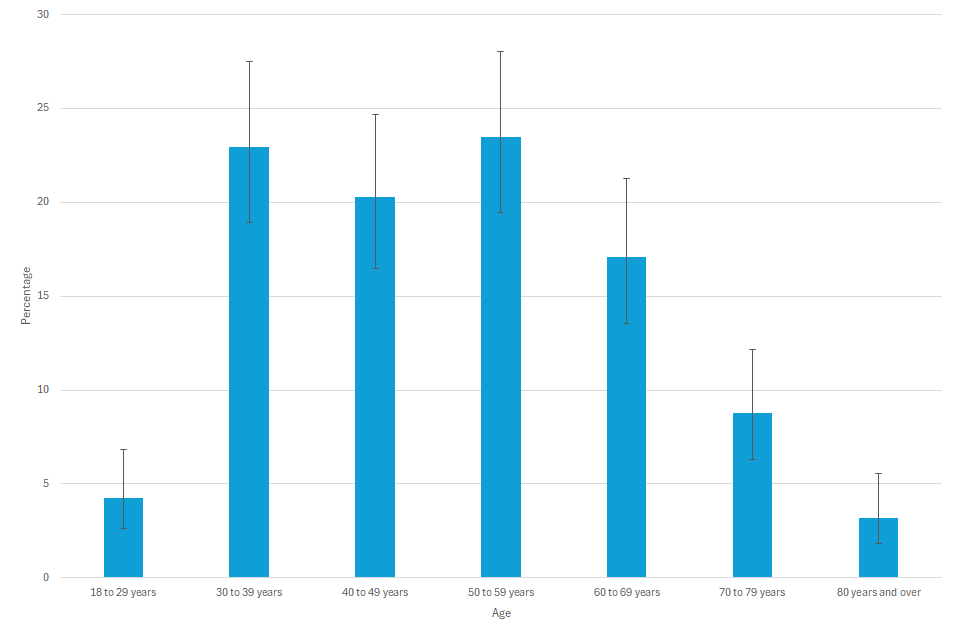

Among UK veterans, those aged 30 to 39 years were more likely to have said they were convicted of a criminal offence (18.8%) than veterans aged 40 years and over.

Figure 2: Veterans aged 80 years and over were least likely to have said they were convicted of a criminal offence

Weighted percentages of veterans who said they were convicted of a criminal offence by age. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

“Age” refers to the age on the last birthday, rather than exact age.

Male veterans were more than 4 times more likely than female veterans to have said they were convicted of a criminal offence (11.3% compared with 2.7%) which reflects the pattern seen for the general population in England and Wales in the Ministry of Justice‚Äôs (MoJ‚Äôs) Statistics on Women and the Criminal Justice System 2023, where 78% of convictions were males.Ã˝

There was no evidence of difference for whetherÃ˝a veteran was convicted before, during or after service by sex or in the proportion of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence before or after service by age. However, those aged 80 years and over were least likely to have been convicted during service (26.4% compared with 47.9% of those aged 30 to 39 years).

Of those who said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence, those aged 30 to 39 years old were the most likely to have ever served a prison sentence (40.3% compared with 18.8% of those aged 80 years and over). Males with a conviction were more likely than females with a conviction to have ever served a prison sentence (25.3% compared with 9.9%), which is expected as HMPPS Offender Equalities Annual Report 2022-23, showed the prison population remained as majority male in 2022-23 and as seen in previous years.

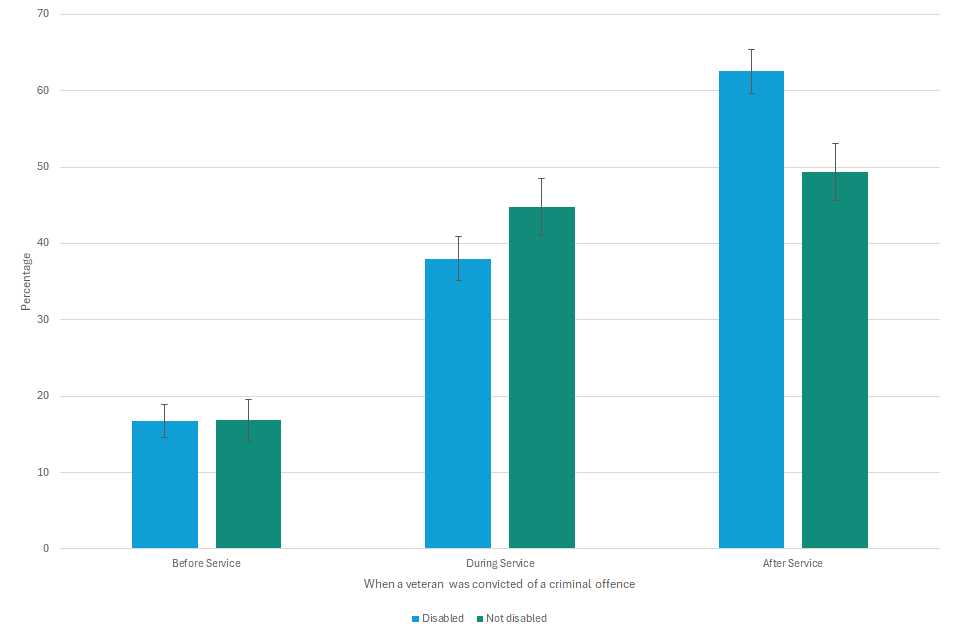

6.2 Disability

Those who were disabled under the Equality Act 2010Ã˝were more likely than those who were not disabled to have said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (12.4% compared with 8.3%). The definition of disability under the Equality Act 2010 includes those with a physical or mental impairment that has a substantial and long-term negative affect on a persons‚Äô ability to do normal daily activities. Existing evidence tells us that in the general population, people with cognitive impairments, mental health conditions and neuro-diverse conditions are overrepresented in the UK criminal justice system, as detailed in .

Disabled veterans who said they were convicted of a criminal offence were more likely than those who were not disabled to have said they were convicted after service (62.5% compared with 49.3%) and less likely to say they were convicted during service (38.0% compared with 44.8%).Ã˝We see a similar pattern for criminal convictions when comparing those who required a personalised care plan to those who did not.

Figure 3: Veterans with a disability were more likely to say they were convicted after service than those without a disability

Weighted percentages of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence by when they were convicted by disability. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Only veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence were asked when they were convicted.

Respondents could have selected as many options as applicable.

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

There was no evidence of difference in the proportion of veterans who had ever served a prison sentence by disability. However, those who required a personalised care plan were more likely to have ever served a prison sentence (32.0%) than those who did not require a personalised care plan (20.6%).

6.3 Sexual orientation

Veterans who identified their sexual orientation as “Straight or Heterosexual” were less likely to have said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (10.5%) than those who identified their sexual orientation as “Gay”, “Lesbian” or “Bi-sexual” (LGB+) (14.5%). Historic law in the UK prohibiting same-sex sexual activity was in place until 1967 and it is feasible some may have a criminal conviction on this basis. There is limited evidence about whether LGB+ individuals are overrepresented in the criminal justice system for the general population; as outlined in HMPPS Offender Equalities Annual Report 2022-23, 3.0% of the general prison population in England and Wales were LGB+.

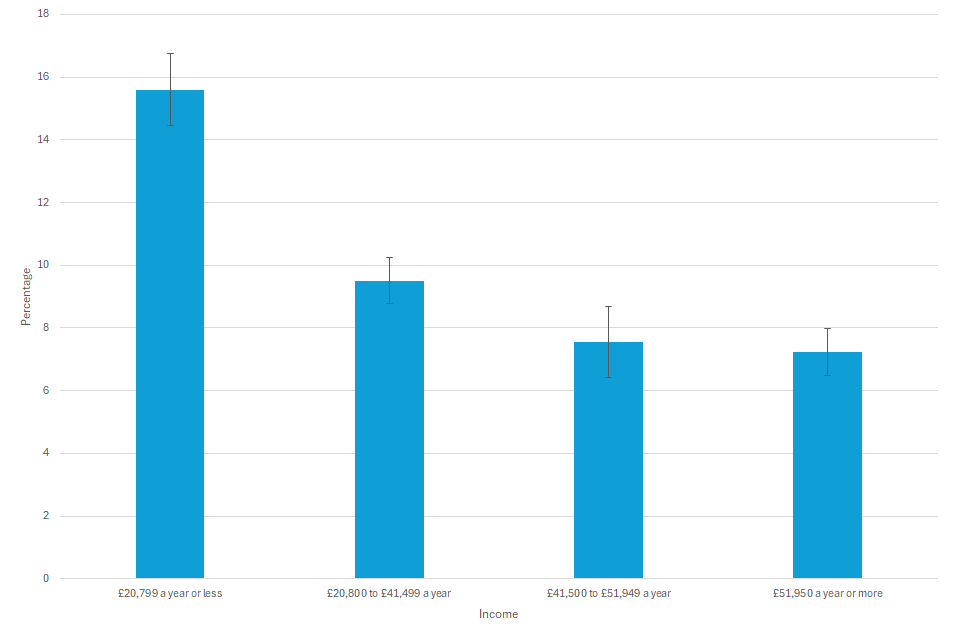

6.4 Finance and employment-related factors

Whether a veteran had ever been convicted of a criminal offence was related to financial factors in the survey. Those who agreed to some extent they had money worries in the last month were more likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence (15.4%) than those who disagreed to some extent (7.5%). Veterans who claimed Universal Credit, Personal Independence Payments or Adult Disability Payment in the last month were also more likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence than those who had not (21.3% compared with 9.5%).

Figure 4: Veterans who had an income of £20,799 a year or less were more likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence than veterans whose income was £20,800 a year or more

Weighted percentages of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence by income. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Veterans who said they had ever taken a job at a lower experience or skill levelÃ˝than their last role in the UK armed forces were more likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence (12.8%) than those who had not taken a job at a lower experience or skill level (7.1%).

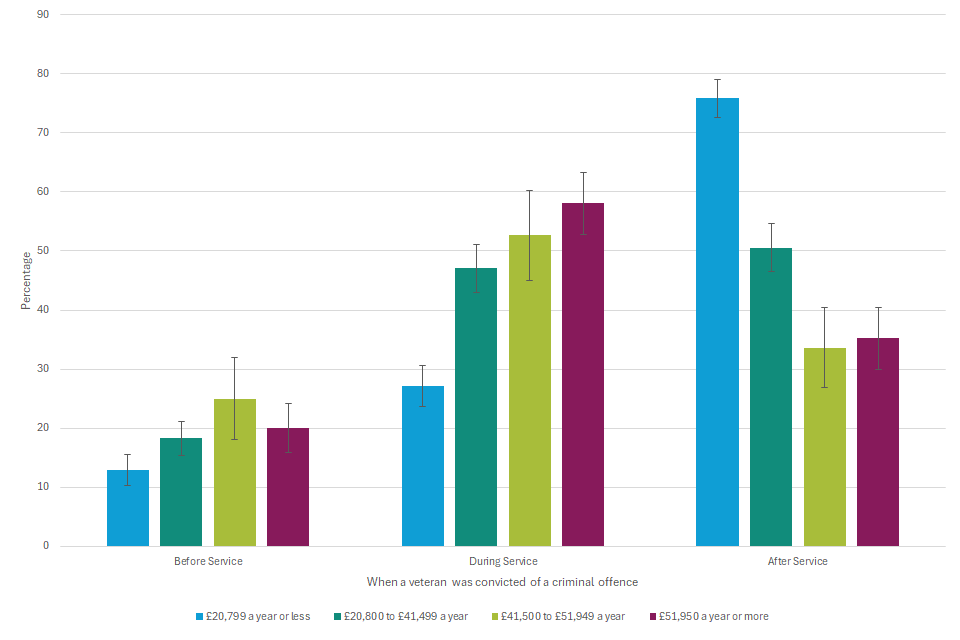

It is not possible to determine cause and effect from survey data and we do not know if lower income, or higher levels of agreement that a veteran had money worries or of skill-related underemployment were because of a criminal conviction or had persisted longer-term and were associated with an increased propensity to have been convicted of a criminal offence.Ã˝However, we do see patterns for the finance variables by those who were ever convicted at different stages. Those whose income was ¬£41,500 a year or more were more likely than those in the lowest income category to have been convicted before service (20.1% of those whose income was ¬£51,950 a year or more compared with 12.9% of those whose income was ¬£20,799 a year or less). It should be noted that recruitment restrictions for the UK armed forces will mean there is a potential difference in the severity of offences that may be referred to in the before service category as compared with the during and after service response options.

Figure 5: Veterans whose income was £20,799 a year or less were more likely to have said they committed an offence after service and less likely to have committed an offence before or during service than those whose income was £51,950 a year or more

Weighted percentages of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence by when they were convicted by income. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Only veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence were asked when they were convicted.

Respondents could have selected as many options as applicable.

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Veterans who had ever taken a job at a lower skill or experience level were more likely to have committed an offence after service (61.0%) than those who had not experienced this so far (46.1%).

Whether a veteran had ever served a prison sentence was strongly associated with income, 38.4% of veterans whose income was £20,799 a year or less had ever served a prison sentence compared with 5.5% of those whose income was £51,950 a year or more. We do not expect these figures to have been impacted by veterans who were in prison at the time of the survey because of the large proportion who had ever served a prison sentence in the “Don’t Know” group for income (72.3%). A similar pattern was seen for whether a veteran agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the past month or whether they disagreed to some extent, where 31.2% had ever served a prison sentence compared with 16.5%, and whether a veteran said they had claimed Universal Credit, Personal Independent Payment or Adult Disability Payment or said they did not (32.6% compared with 23.0%).

7. Findings: Criminal convictions and prison sentences by service-related factors

7.1 Service type

There was no evidence of difference in the proportion of veterans who said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence by service type. However, veterans who served as a Regular only were less likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence before service (14.9%) than those who served as a Reserve only (30.0%) or both Regular and Reserve (23.3%). There were minimal differences by service type for veterans who said they were convicted during or after service.

7.2 Service branch

Those who had served in the British Army or Royal Marines were most likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence (12.7% and 16.4% respectively), followed by those who served in the Royal Navy (7.7%), and those who had served in the Royal Air Force were least likely (5.7%). There was no evidence of difference in when a veteran said they were convicted by service branch or in the proportion of veterans who had ever served a prison sentence by service branch.

7.3 Rank

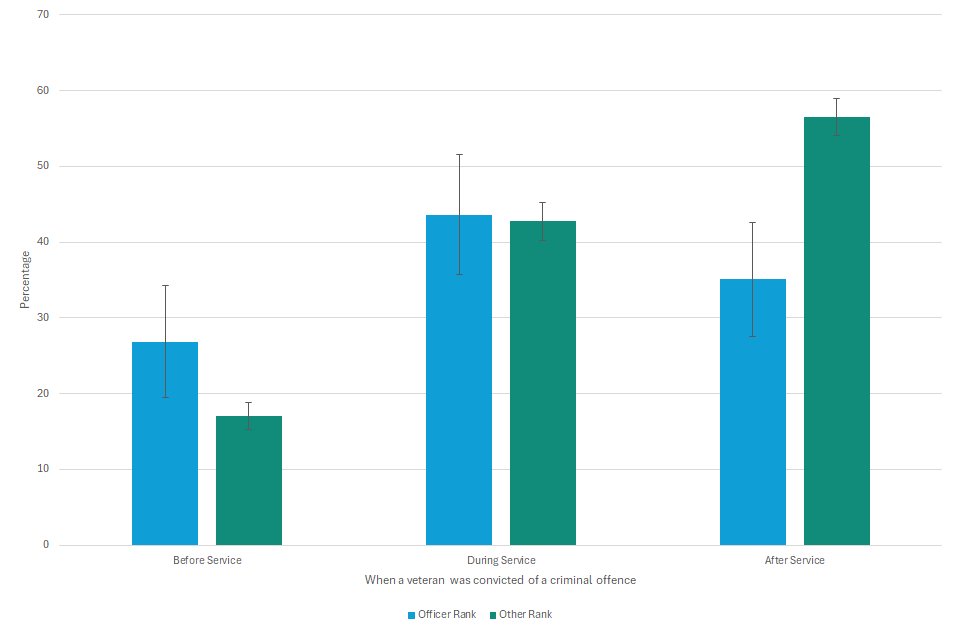

Veterans who said they served at Officer ranks were less likely than those who served below Officer ranks to have been convicted of a criminal offence (2.9% compared with 11.6%). Among veterans who had ever been convicted of a criminal offence, those who served at Officer ranks were more likely to have been convicted before service than those who served below Officer ranks (26.9% compared with 17.1%) and less likely to have been convicted of an offence after service (35.1% compared with 56.6%).

Those who served at Officer ranks were also less likely to have ever served a prison sentence (4.9%) than veterans who served below Officer ranks (16.4%).

Figure 6: Veterans who served at Officer ranks were more likely to have been convicted before service and less likely to have been convicted after service than those who served below Officer rank

Weighted percentages of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence by when they were convicted by rank. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Only veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence were asked when they were convicted.

Respondents could have selected as many options as applicable.

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

7.4 Veterans who served for less than 4 years

While 5.3% of those who served 25 years or more said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence, 15.5% of those who served for less than 4 years had ever been convicted. Veterans who served for less than 4 years include those who might be classed as Early Service Leavers as well as those who may have served as part of National Service. Veterans who served as part of the National Service were less likely to have said they were convicted than all other veterans (4.1% compared with 10.8%), so we expect the higher proportion of veterans that had ever been convicted of a criminal offence amongst those that served less than 4 years to be predominantly related to the Early Service leavers within this group. Veterans who served for less than 4 years were most likely to have ever served a prison sentence (62.1% compared with 9.1% of those who served for 25 years or more).

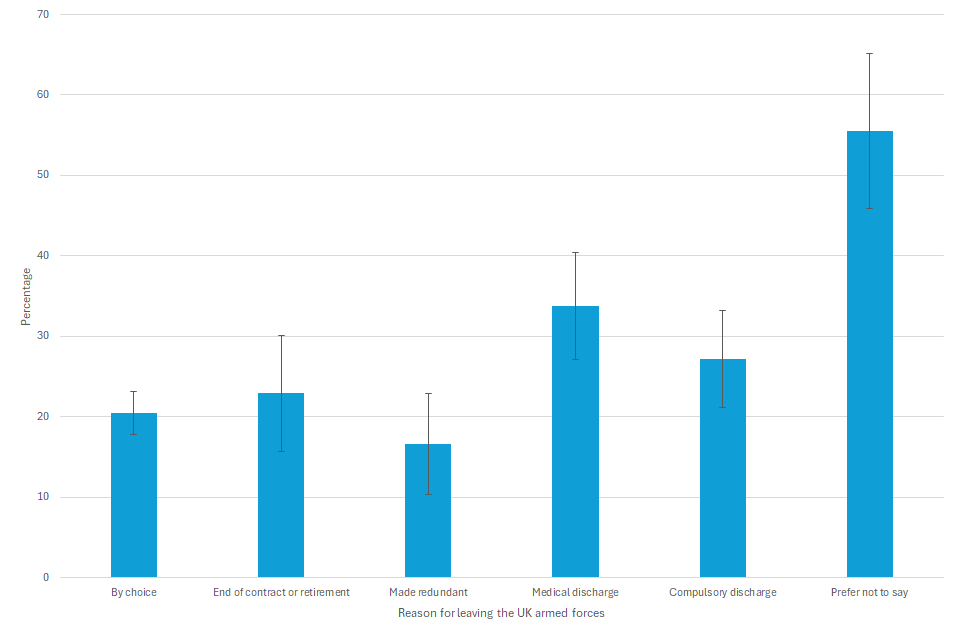

7.5 Reason for leaving the UK armed forces

Those who left due to medical discharge or preferred not to say their reason for leaving were more likely to have been convicted (15.9% and 19.7% respectively) than those who gave any other known reason for leaving (9.5% for left by choice, 8.8% for end of contract or retirement, 10.2% for those made redundant and 11.2% for compulsory discharge).

There were minimal differences between reason for leaving the UK armed forces for those who said they were convicted before or after service but as expected, those who left by compulsory discharge were more likely to have been convicted during service (54.9%) than those who left by choice (37.6%), made redundant (39.3%), medical discharge (36.6%) or preferred not to say why they left (35.1%).

Veterans who preferred not to say why they left the UK armed forces were more likely than all other veterans to have said they had ever served a prison sentence.

Figure 7: Veterans who left by medical discharge were more likely to have ever served a prison sentence than those who left by choice or who were made redundant

Weighted percentages of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence that had ever served a prison sentence by reason for leaving service. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Only veterans who said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence were asked if they had ever served a prison sentence, this included those who were currently serving a prison sentence at the time of the survey,

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

7.6 Experience during service

Veterans who had been deployed on named operations were more likely than those who had not to have been convicted of a criminal offence (11.0% compared with 8.7%) and veterans who said they had witnessed or took part in operations against enemy forces were more likely to have been convicted than those who had not (12.2% compared with 7.8%).

There was no evidence of difference in the proportion of veterans who were ever convicted before service by whether a veteran was deployed but those who were deployed on Operational Deployment were more likely to have been convicted during service (46.3%) and less likely to have been convicted after service (52.9%) than those who were not deployed (21.3% and 73.5% respectively). Veterans who had been deployed on Operational Deployment were also more likely to have served a prison sentence than those who had not (40.1%Ã˝compared with 18.3%).

7.7 Transition to civilian life

Veterans who said they felt unprepared to some extent for life after service in the UK armed forces were more likely than those who felt prepared to some extent to have been convicted of a criminal offence (15.1% compared with 6.9%).

Veterans who felt unprepared to some extent to leave the UK armed forces were more likely to have been convicted after service (64.8%) than those who felt prepared to some extent (47.3%). There was no evidence of difference in the proportion of veterans who had ever served a prison sentence by how prepared or unprepared a veteran felt for life after service.

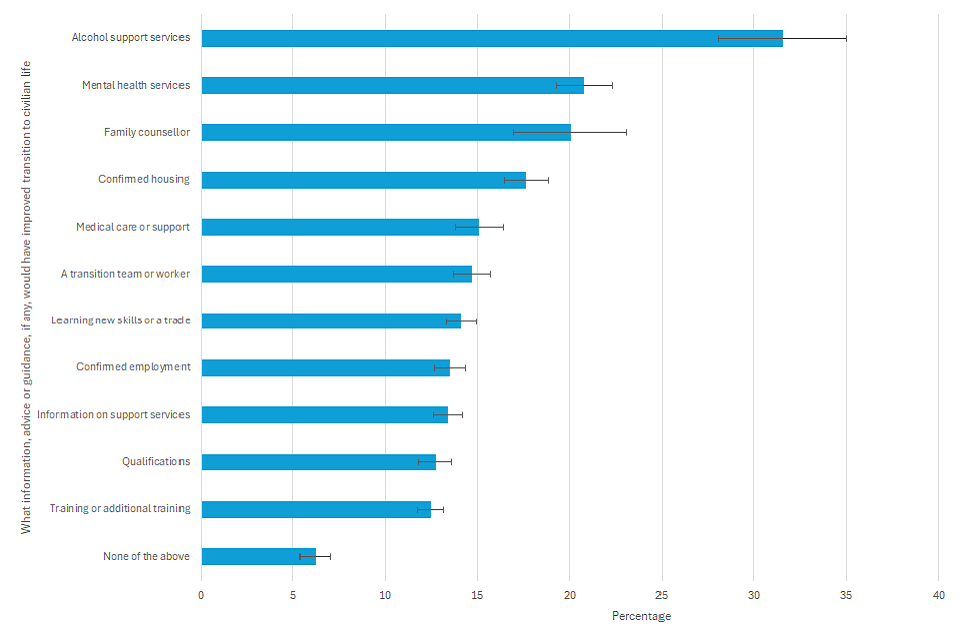

Among UK veterans, those who said alcohol support services would have improved their transition were the most likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence (28.1%).

Figure 8:Ã˝Veterans who said alcohol support services would have improved their transition were the most likely to have been convicted of a criminal offence

Weighted percentages of veterans who were ever convicted of a criminal offence by what information, advice, or guidance, if any, would have improved transition to civilian life. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Respondents could have ticked as many response options as applied to the question: ‘What information, advice or guidance, if any, would have improved transition to civilian life?’

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Among those who had ever been convicted of a criminal offence, there was no evidence of difference in the proportions who said they were convicted of an offence before service by what they said would have improved their transition to civilian life and there were minimal differences in the proportions who said they were convicted of an offence during service. However, those who said alcohol support or confirmed housing would have improved their transition were more likely to have said they were convicted of a criminal offence after service (73.5% and 70.1% respectively) than those who mention any other types of support except mental health and family counselling.

There were minimal differences in the proportion of veterans who had ever served a prison sentence by what veterans said would have helped improve transition.

8. Coverage: Veterans who were currently serving a prison sentence

Among UK veterans in the survey, 1.7% were in prison at the time of the survey. This is larger than the proportion recorded in where 0.2% of veterans were recorded in prison in England and Wales. It should be noted that a paper copy of the survey was specifically sent into prisons across the UK to ensure this group of veterans was captured (more information about how the survey design can be found in Office for National Statistics’ (ONS’s) ). Additionally in Census 2021, those who were serving 12 months or less were enumerated at their home address where applicable and this means not all veterans in prison will have been captured in the data.

The following analysis is intended to explain more about veterans who responded to the survey from prison and about their views, it is not intended to be used as an estimate of the proportion of veterans who were serving a prison sentence. There is no way to understand how representative these data are of the actual veteran population who were in prison at the time of the survey. Analysis of veterans who were serving a prison sentence at the time of the survey remains unweighted.

8.1 Age

Veterans currently in prison were most likely to be aged 30 to 69 years, which is younger than veterans in general. The proportion of veterans currently in prison by age was similar in , and HMPPS Offender Equalities Annual Report 2022-23 shows among the general population 30 to 39 years was the largest age group, followed by 40 to 49 years.

Figure 9: Veterans who were serving a prison sentence at the time of the survey were most likely to be aged 30 to 69 years old

Unweighted percentage of veterans who were serving a prison sentence at the time of the survey by age. Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: The Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Percentages of veterans who were serving a prison sentence at the time of the survey are unweighted.

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked whether they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence (excluding speeding offences).

Only veterans who said they had ever been convicted of a criminal offence were asked if they had ever served a prison sentence and only those who had ever served a prison sentence were asked if they were currently in prison.

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

“Age” refers to the age on the last birthday, rather than exact age.

8.2 Disability

Veterans currently in prison were more likely to have been disabled (55.9%) than not disabled (39.7%). This is higher than the proportion estimated for the general population in the Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction (SPCR) survey in 2012, Estimating the prevalence of disability amongst prisoners.

8.3 When a veteran was convicted of a criminal offence

Of veterans in prison at the time of the survey, 7.5% had ever been convicted of an offence before service, 19.5% had ever been convicted of an offence during service and 84.5% had ever been convicted of a criminal offence after service.

8.4 Community belonging, trust in government and loneliness

Of those who were currently serving a prison sentence, 72.0% agreed to some extent that they did not have any say in what the government did, and they were more likely to have disagreed to some extent that they felt like they belonged to their local community (38.0%) than to have agreed to some extent (28.1%).

Nearly two-thirds of veterans currently in prison felt lonely always, often or some of the time (62.6%).

8.5 Service-related factors

Veterans currently in prison were most likely to have only served in the Regular armed forces (83.4%), which is similar to the general veteran population as outlined in . Veterans currently in prison were also most likely to have served in the British Army (78.8%), the British Army make up the largest proportion of the UK armed forces personnel as reported in the Quarterly service personnel statistics from the Ministry of Defence.

We know veterans in prison are typically younger than the general veteran population and those who served in the British Army have a younger age profile than those who served in the Royal Air Force, Royal Navy or Royal Marines.

Over a third of veterans who were currently in prison served in the UK armed forces for less than 4 years (36.8%), and they were more likely to have been deployed on Operational Deployment (54.0%) and to have witnessed or taken part in operations against enemy forces (72.9%) than to have not experienced either of these (37.9% and 17.2% respectively). Less than 1 in 10 veterans currently in prison said they were subject to harassment or sexual harassment (7.7%), 18.9% said they were subject to discrimination and 23.8% said they were subject to bullying during service.

Over half of veterans currently in prison said they left the UK armed forces 20 years or more ago (58.1%) and the most common reason for leaving was by choice (44.1%).

Half of veterans currently in prison said they felt unprepared to some extent for life after service (50.0%), compared with 20.7% who felt neither prepared nor unprepared and 26.4% who felt prepared to some extent. Of those who were currently in prison, 43.7% had looked for help from a veteran or service charity.

8.6 Specialist support services for veterans in prison

Just under two-thirds (62.1%) of veterans in prison said they had accessed specialist support while in prison. They were also asked what support services they had used and were able to provide a free text write in response. Of those who responded to this question over a third said they had used support from Soldiers’, Sailors’, and Airmen’s Families Association (SSAFA), a fifth said they has used support from Care after Combat and 1 in 10 said they had accessed support through Veterans in Custody. Smaller proportions of veterans referenced Veterans UK, Veterans First and The Royal British Legion (RBL).

8.7 Veterans in prison: services and support that would be helpful that is currently lacking

Qualitative analysis of the question: “Can you tell us what service or support would have been helpful for you that is currently lacking?” has been completed for respondents who were serving a prison sentence at the time of the survey. Details on how the qualitative analysis has been completed can be found in the Data sources and quality section. Content analysis of these responses is unweighted. Full descriptions for each theme are in Glossary: qualitative themes.

Of veterans currently in prison who answered the question about what was currently lacking, over a third mentioned housing in their response, around 1 in 5 said health (mainly mental health) and over 1 in 10 said careers or finance.

“Housing and counselling for veterans.”

“Someone to talk to and believe me. Help with medical.”

Veterans could respond about support that they felt was lacking at any point in time for them since leaving service, and many responses included what would be helpful to prepare them for leaving prison with a specific focus on housing and career support.

“Careers after prison.”

“To find housing whilst in prison.”

“Advice on local issues after release from HMP.”

Health and mental health support being lacking was referenced in relation to the past tense as well as the present tense.

“Awareness, it took for me to be a criminal to ask for help.”

“As a prisoner more support, mentally, financially, physically.”

“More available help for Vets in custody (especially England).”

9. Future publications

Findings from the Veterans’ Family Survey 2022 will be published in 2025.

10. Data

Dataset | Released on 10 June 2025Ã˝

UK armed forces veterans by convictions of a criminal offence by personal and service-related characteristics, weighted estimates, from the Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Dataset | Released on 10 June 2025

UK armed forces veterans who had ever been convicted and whether they had ever served aÃ˝prison sentence, by personal and service-related characteristics, weighted estimates, taken from the Veterans‚Äô Survey 2022, UK.Ã˝

Dataset | Released on 10 June 2025Ã˝

UK armed forces veterans who had ever been convicted and who were serving a prison sentence, by personal and service-related characteristics, unweighted estimates, taken from the Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

11. Glossary

11.1 Confidence intervals

Veterans’ Survey 2022 estimates are presented in our data with 95% confidence intervals. At the 95% confidence level, over many repeats of a survey under the same conditions, one would expect that the confidence interval would contain the true population value 95 times out of 100. Confidence intervals presented are based on complex standard errors (CSEs) around estimates. These reflect the design effects calculated for England and Wales Veterans’ Survey 2022 data, as outlined in the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS’s) .

11.2 Deployment

Respondents who were completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked “During your service did you deploy on an Operational Deployment (named operations)?”

All respondents who said they were deployed on an Operational Deployment (named operation) were also asked: “Did you witness or take part in operations against enemy forces?”

11.3 Disability

People who assessed their day-to-day activities as limited by long-term physical or mental health conditions or illnesses are considered disabled. This definition of a disabled person meets the harmonised standard for measuring disability and is in line with the Equality Act 2010.

11.4 Early Service Leavers

Early Service Leavers are UK armed forces veterans who have chosen to leave or have been discharged from the UK armed forces before completing an initial 4 years of service.

11.5 Economic activity status last week

Veterans aged 18 years and over were classified as ‘working’ if they were economically active and in employment in the previous 7 days.

‘Unemployed’ refers to people who said they were out of work during the same period but were either looking for work, and could start within 2 weeks, or were waiting to start a job that had been offered and accepted.

‘Economically inactive’ refers to veterans aged 18 years and over who did not have a job in the previous 7 days, and who had not looked for work in the previous 4 weeks or could not start work within 2 weeks.

11.6 LGB+

An abbreviation used to refer to people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other minority sexual orientations (for example, asexual).

11.7 Personalised care plan

The personalised care plan question asked of all respondents was: “Do you have complex and long-term healthcare needs that require a personalised care plan to support your health and wellbeing?”.

Respondents were informed that personalised care planning is essentially about addressing an individual’s full range of healthcare needs, treating the person “as a whole”, with a strong focus on helping people, together with their carers to achieve the outcomes they want for themselves.

11.8 Rank

A veteran-specific derived variable was created for rank. This derived variable was designed to differentiate between commissioned officer and non-officer ranks. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) worked with the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and the Office for Veterans’ Affairs (OVA) to group the list of ranks for each service type into these categories. There were a small number of responses that could not be coded appropriately, and these are excluded from our analysis for this publication.

11.9 Reason for leaving

All respondents were asked: “For what reason did you leave the UK Armed Forces?”. Response options were:

- “By choice”

- “End of contract or retirement”

- “Made redundant”

- “Medical discharge”

- “Compulsory discharge”

- “Prefer not to say”

11.10 Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is a term covering sexual identity, attraction, and behaviour. For an individual respondent, these may not be the same. For example, someone in an opposite-sex relationship may also experience same-sex attraction, and vice versa. This means the statistics should be interpreted purely as showing how people responded to the question, rather than being about who they are attracted to or their actual relationships.

We have not provided glossary entries for individual sexual orientation categories. This is because individual respondents may have differing perspectives on the exact meaning.

11.11 UK armed forces veteran

This analysis defines veterans as people aged 18 years and over who have previously served in the UK armed forces. This includes those who have served for at least one day in the UK armed forces, either regular or reserves, or merchant mariners who have seen duty on legally defined military operations. The Veterans’ Survey 2022 only includes veterans aged 18 years and over because of the nature of the active combat and wellbeing questions.

It does not include those who have left and since re-entered the regular or reserve UK armed forces, those who have only served in foreign armed forces, or those who have served in the UK armed forces and are currently living outside of the UK.

12. Glossary: qualitative themes

12.1 Careers

Veterans said that they did not find the support they had received to be sufficient. This was sometimes because of timeliness. Veterans said they did not have the opportunity to engage fully with the support before leaving or they said the support should be for a longer period post-transition, with some saying the support should be continuous. This theme also included references in relation to the quality of the career transition support veterans felt they received. Some veterans felt they were pigeonholed into certain types of careers, based on pre-conceptions about their likely skill sets.

There were also many suggestions of what veterans felt would help more. Some examples include:

- better links with veteran-friendly employers

- better communication by the government with employers to dispel pre-conceptions of veterans who they felt could sometimes hinder them

- mentors with a military background who have built successful careers following their transition

- workshops and careers fairs with veteran-friendly employers

- job placements before leaving

- ongoing, time-unlimited veteran careers networks

Networking, interviewing, and CV writing skills were also referred to.

12.2 Finance

This theme includes all mentions of financial advice and assistance. It was often referenced alongside housing, education, or pension themes. This theme relates to a need to improve overall financial literacy training as part of transition out of the UK armed forces. This included references to understanding the pitfalls of borrowing, planning, saving, mortgages, tax (with specific references to self-employment) and financial planning for retirement. This also involves help with understanding and accessing the benefits system, and actual funding and grants. Funding or grants were specifically mentioned in relation to training and retraining or education and housing, in relation to assistance with necessary purchases for health-related issues, like hearing aids, mobility scooters, or home modifications, and in relation to general help with the cost of living.

12.3 Health all

This was a broad, high-level category that covered many aspects of support for veteran health. There were specific references to different elements of health, and we identified several sub-themes. Among those who talked about inadequate health services, many spoke about mental health services in particular. They also spoke about issues with the NHS, specifically issues with transitioning to civilian medical care. Many veterans mentioned issues with dentist services.Ã˝Other sub-themes within the theme of health included statements about a lack of health services available in relation to support for injuries or wellness issues that veterans felt had been a direct result of their service. Some specifically mentioned needing support for hearing loss, disability, the War Pension Scheme, and of a need for continuity of care through better access to service medical records.

12.4 Housing

This is a broad theme that covers any mentions of improved support for finding housing, both in terms of providing veterans with better, more timely information, and in relation to actual prioritisation of housing services and provision of veteran-specific schemes. Often veterans will have just stated “housing”. Where more context was given, it often related to provision of support to those who were leaving the UK armed forces and trying to secure accommodation while also seeking a job, and that this was difficult to do simultaneously. Some referenced a need for confirmed housing upon leaving the UK armed forces for an interim period while a veteran found work. There were calls for more support in supplying both information about and the actual provision of social, council or affordable housing for veterans. Some veterans said they feel they should be supported to get on the property ladder and help to buy and shared ownership schemes for veterans were referenced. More transparency on assistance with housing for veterans and their families was referenced, including better protection from bad landlords and better provision for people living in unsuitable accommodation. Many veterans also said more needs to be done to support homeless veterans.

12.5 Mental health

Mental health was also often linked in comments about the NHS with many veterans saying the support available on the NHS and waiting times, combined with a lack of understanding by NHS professionals about military experiences and operations, made treatment of conditions such as Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder less effective.Ã˝

13. Data sources and quality

13.1 Data

Veterans in this research have been identified using the Veterans’ Survey 2022. For more information, see our .

13.2 Quality

Weighting for England and Wales Veterans‚Äô Survey, 2022Ã˝

The age profile of veterans responding to the survey differed from the age profile of veterans identified in Census 2021. Survey respondents were younger than veterans from Census 2021. This may reflect the fact the survey was mainly online, or that marketing and promotion of the survey was more likely to reach younger veterans.

We used raking techniques to generate weights for England and Wales survey responses. This was based on the proportions of veterans we would expect to be within given age bands when we considered the age range of veterans from Census 2021. You can read more about this in our Veterans’ Survey methodology.

Northern Ireland and Scotland, Veterans’ Survey 2022

There were no reliable veteran population data available for Northern Ireland or Scotland that we could use to assess the representativeness of responses to the Veterans’ Survey from people who lived in these countries. Veteran population data from the Scotland Census 2022 were not available at the time the survey data were processed and weighted.

Responses from Northern Ireland and Scotland remain unweighted. This principle was maintained, even when a respondent gave a postcode that suggested they had an alternative address in England or Wales. However, assumptions are made about bias in respondent profiles from Northern Ireland or Scotland. This is based on biases we identified in the survey respondents’ profiles from England and Wales, compared with data from Census 2021. This gives us a strong understanding of the veteran population in England and Wales.

We have also assumed additional uncertainty because of the sample design based on England and Wales data. We have included a design effect in the origin of complex standard errors for UK-level Veterans’ Survey 2022 data. You can read more about this in our Veterans’ Survey methodology.

Bias in sample profile, Veterans’ Survey 2022

Despite weighting the data to compensate for known biases in the Veterans’ Survey 2022, some biases remain, as outlined in our . Awareness of these biases can be used to help interpretation of results and to guide future analysis.

Unweighted analysis of veterans currently in prison

Analysis of veterans who were serving a prison sentence at the time of the survey remains unweighted because of to lack of comparable data about veterans currently in prison, more information can be found in Coverage: Veterans currently serving a prison sentence section.

Statistical disclosure control

To ensure statistical disclosure conditions are met in our UK analysis, we do not publish estimates for data based on fewer than 3 respondents.

Country-level data is not available for those who ever served a prison sentence or were currently in prison due to small numbers. Findings by country for whether a veteran was ever convicted of a criminal offence are described in the .

Qualitative analysis

Veterans were asked a more generic question about services and support: ‚ÄúCan you tell us what service and support would have been helpful for you that is currently lacking?‚Äù. This question asked for free text, qualitative responses. Respondents could have responded in relation to their needs at any stage of life.Ã˝

To report on the themes in an interest group, we took all the veteran responses and removed blank responses to the question and responses that stated the respondent did not have an answer or did not know. The remaining veteran responses were then filtered to the interest group and the most prevalent themes within this interest group were discussed. Each response could be classified to multiple themes, where applicable. Content analysis of these responses is unweighted.

14. Related links

Employment, skills, and volunteering of UK armed forces veterans

Article | Released 23 April 2025

This report provides analysis of responses to the Veterans’ Survey 2022, with focus on:

- employment

- skills

- volunteering

Estimates of veteran responses are provided by personal and service-related characteristics. All UK estimates are weighted. Qualitative analysis contained in this report is unweighted.

Finance and housing of UK armed forces veterans

Article | Released 10 January 2025

This report provides analysis of responses to the Veterans’ Survey 2022, with focus on:

- income and money worries

- veterans who were homeless, rough sleeping, living in a refuge for domestic abuse and living long-term with family or friends

Estimates of veteran responses are provided by personal and service-related characteristics. All UK estimates are weighted percentages. Qualitative analysis contained in this report is unweighted.

Health and wellbeing of UK armed forces veterans

Article | Released 4 December 2024

This report provides analysis of responses to the Veterans’ Survey 2022, with focus on:

- Health

- wellbeing

- GP and dentist registrations

Estimates of veteran responses are provided by personal and service-related characteristics. All UK estimates are weighted. Qualitative analysis contained in this report is unweighted.

Preparedness to leave the UK armed forces

Article | Released 22 August 2024

This report provides analysis of responses to the Veterans’ Survey 2022, with a focus on:

- preparedness to leave the UK armed forces

- types of information, advice or guidance that would have improved transition

Estimates of veteran responses are provided by personal and service-related characteristics. All UK estimates are weighted. Qualitative analysis contained in this report is unweighted.

Life after service in the UK armed forces

Article | Released 9 August 2024

This report provides analysis of responses to the Veterans’ Survey 2022, with a focus on:

- where veterans accessed information about veteran-related issues, services or benefits

- use of veteran or service charities

- awareness, use and satisfaction of Veterans UK and Veterans’ Gateway

- community engagement

Estimates of veteran responses are provided by personal and service-related characteristics. All UK estimates are weighted.

Ã˝

Article | Released 15 December 2023

Coverage and sample bias analysis of the Veterans‚Äô Survey 2022, with weighted estimates for veteran responses in the UK by personal characteristics.Ã˝

Ã˝

Methodology | Released 15 December 2023

Quality of the linkage between Census 2021 and the Veterans‚Äô Survey 2022 and main findings.Ã˝

Methodology | Released 15 December 2023

Ã˝

Overview of the development, processing, data cleaning and weighting of the Veterans‚Äô Survey 2022.Ã˝

Ã˝

Methodology | Released 16 March 2022Ã˝

Detail on how the measurement of previous UK armed forces service has been made more comparable, consistent, and coherent.